5. Positive Space

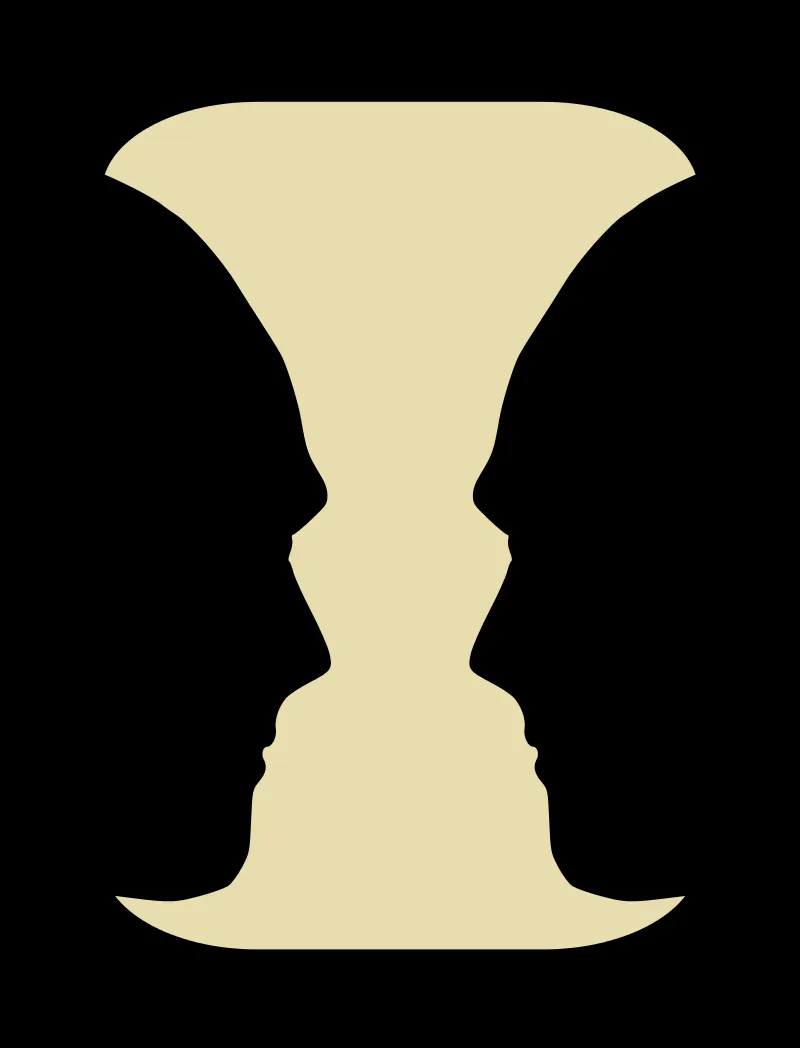

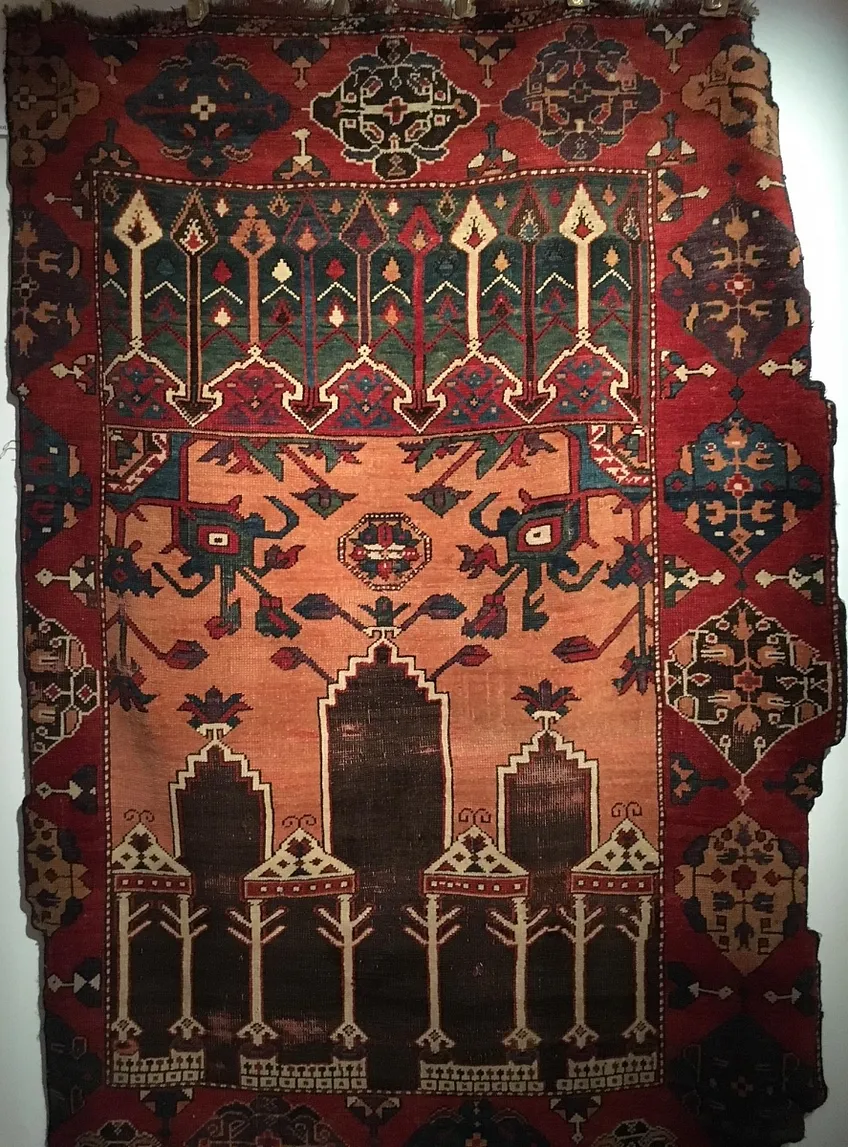

Neighboring centers help each other come to life when they are shaped so each one is positive—relatively simple, convex, and locally symmetrical. Positive centers are easy to perceive as foreground figures. They aren’t mere leftover scraps. They have presence; they feel coherent and purposeful. In order for positive space to be present, even the “background” of a design must be positive.

What does it mean for code to evince this property? Recall that the major centers in code are tokens, statements, blocks, functions, objects, and modules. A center in code is positive when it is coherent within itself, uncomplicated by outside concerns nosing in. Functions, methods, classes are inward-looking. Parameter names, function names, and comments don't refer to the functions' callers. It becomes easier to understand each center when it is coherent, centered in itself, even though it is related to and supported by many other centers.

Positively shaped code is neighborly. It takes its shape while allowing its neighbors to take theirs.

Here’s a simple example: a removePrefix function, from my book-compiler mdsite. You can probably understand what this code does, and perhaps imagine using it in your own software, without knowing anything about the program it’s from.

export function removePrefix(s: string, prefix: string): string {

if (s.startsWith(prefix)) {

return s.slice(prefix.length);

} else {

return s;

}

}

In all these cases, the positiveness of the space — what we might also call the convexity and compactness of the centers which form — is the outward manifestation of internal coherence in the physical system.

—Christopher Alexander, The Phenomenon of Life, p. 262

Positive shape is related to the balanced abstraction principle, which says that each center in code should be written at a consistent level of abstraction. For example, code that reads and writes files should just know about files; it shouldn’t also know about application-specific details like what data is in those files. Conversely, code that deals with concepts in the application domain shouldn’t know about details of infrastructure like files, HTTP requests, or databases. Mixing levels of abstraction compromises positive shape, making code harder to understand and modify. You have to read more and can reuse less.

Positive shape has a pleasant symbiosis with unit testing. Because positively-shaped centers are easy to conceptualize and reason about in isolation, they are easy to test, and it is easy to see that the tests specify the right behavior. You can compose positively-shaped centers and have confidence that the whole will do what you expect, even without comprehensive integration tests.

Positively-shaped code often feels like it could be part of the language or the standard library. It “brings the language up to meet the problem,” abstracting away the nitty-gritty details and distilling the code to its essence. Positive shapes intensify precision and clarity.

Good abstractions are positive in this way. As Dijkstra put it:

The purpose of abstraction is not to be vague, but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise.

—Edsger Dijkstra

Katrina Owen gives a good example of what code looks like when it is not positively shaped, in “What’s in a Name: Anti-patterns to a Hard Problem.” She calls this specific antipattern an idea fragment.

# Bad code; negative shape

def prev_or_next_day(date, date_type)

date_type == :last ? date.prev_day : date.next_day

end

This Ruby method comes from a meetup-scheduling app. Dissociated from its context, it makes little sense. It’s unlikely to help you chunk the larger program into brain-sized pieces. You basically have to memorize its implementation and recall it whenever you see the name prev_or_next_day.

Most negatively-shaped code is like this. It seems to have tendrils of other ideas creeping into it. There’s no way to remove it from its context, either mentally or actually, because it’s too tightly bound to the idiosyncratic needs of its callers. And the code that calls negatively-shaped code is damaged as well: because the negatively-shaped dependencies aren’t coherent abstractions, you have to understand their internals before you can make sense of the calling code.

Positive space, then, is the property that appears in code when we can reason about each part in isolation.